Safeguarding Policy

The Limbless Association takes very seriously its responsibility to keep safe the vulnerable adults with whom it supports and works alongside. The charity acknowledges its duty to act appropriately in the event of any safeguarding concerns and allegations, reports or suspicions of a safeguarding matter. With this in mind the LA has developed its Safeguarding Vulnerable Adults Policy that can be read here. It is important to have the policy and procedures in place so that staff, volunteers, service users and carers, and the management committee can work to prevent abuse and know what to do in the event of abuse.

Our policy and procedures cover a variety of safeguarding issues and all of our staff and trustees receive safeguarding training tailored to their roles within the charity.

If you need to raise a concern about someone’s welfare, please contact us and share the information as soon as you can. 0800 644 0185.

Do you have concerns about an adult?

Safeguarding is everyone’s responsibility.

If you have concerns about an adult’s safety and/or wellbeing, you must act on these.

It is not your responsibility to decide whether or not an adult has been abused. It is, however, your responsibility to act on any concerns.

Introduction

Limbless Association is committed to creating and maintaining a safe and positive environment and accepts its responsibility to safeguard the welfare of all adults it supports and who are involved in its services, projects and activities, in accordance with the Care Act 2014. This includes service users, beneficiaries, members, volunteers and employees.

Limbless Association safeguarding adults policy and procedures apply to all individuals involved in the charity.

Limbless Association will encourage and support partners and stakeholders to adopt and demonstrate their commitment to the principles and practice of equality as set out in this safeguarding adults policy and procedures.

1. Principles

The guidance given in the policy and procedures is based on the following principles:

• All adults, regardless of age, ability or disability, gender, race, religion, ethnic origin, sexual orientation, marital or gender status have the right to be protected from abuse and poor practice and to be supported and participate in an enjoyable and safe environment.

• Limbless Association will seek to ensure that our services, support and activities are inclusive and make reasonable adjustments for any ability, disability or impairment. We will also commit to continuous development, monitoring and review.

• The rights, dignity and worth of all adults will always be respected.

• We recognise that ability and disability can change over time, such that some adults may be additionally vulnerable to abuse, in particular those adults with care and support needs.

• We all have a shared responsibility to ensure the safety and well-being of all vulnerable adults and will act appropriately and report concerns whether these concerns arise within the Limbless Association, in the charity’s operating environment or in the wider community.

• All allegations will be taken seriously and responded to quickly in line with Limbless Association Safeguarding Adults Policy and Procedures.

Limbless Association recognises the role and responsibilities of the statutory agencies in safeguarding adults and is committed to complying with the procedures of the respective Local Safeguarding Adults Boards where its services and activities take place.

The six principles of adult safeguarding

The Care Act 2014 sets out the following principles that should underpin safeguarding of adults:

• Empowerment – People being supported and encouraged to make their own decisions and informed consent.

• Prevention – It is better to take action before harm occurs.

• Proportionality – The least intrusive response appropriate to the risk presented.

• Protection – Support and representation for those in greatest need.

• Partnership – Local solutions through services working within their communities. Communities have a part to play in preventing, detecting and reporting neglect and abuse.

• Accountability – Accountability and transparency in delivering safeguarding.

Making Safeguarding personal

‘Making safeguarding personal’ means that adult safeguarding should be person led and outcome focussed. It engages the person in a conversation about how best to respond to their safeguarding situation in a way that enhances involvement, choice and control. As well as improving quality of life, well-being and safety.

Wherever possible discuss safeguarding concerns with the adult to get their view of what they would like to happen and keep them involved in the safeguarding process, seeking their consent to share information outside of the organisation where necessary.

Wellbeing Principle

The concept of wellbeing is threaded throughout the Care Act and it is one that is relevant to adult safeguarding in the context of the services, projects and activities delivered by the Limbless Association. Wellbeing is different for each of us however the Act sets out broad categories that contribute to our sense of wellbeing. By keeping these themes in mind, we can all ensure that our services, projects and activities operate with the principle of inclusivity and wellbeing for all those we support and who participate in activities run by the Limbless Association.

• Personal dignity (including treatment of the individual with respect)

• Physical and mental health and emotional wellbeing

• Protection from abuse and neglect

• Control by the individual over their day-to-day life (including over care and support provided and the way they are provided)

• Participation in work, education, training or recreation

• Social and economic wellbeing

• Domestic, family and personal domains

• Suitability of the individual’s living accommodation

• The individual’s contribution to society.

2. Guidance and Legislation

The practices and procedures within this policy are based on the principles contained within the UK legislation and Government Guidance and will work in unison with the Safeguarding Adults Boards policy and procedures. They take the following into consideration:

• The Care Act 2014

• The Protection of Freedoms Act 2012

• Domestic Violence, Crime and Victims (Amendment) Act 2012

• The Equality Act 2010

• The Safeguarding Vulnerable Groups Act 2006

• Mental Capacity Act 2005

• Sexual Offences Act 2003

• The Human Rights Act 1998

• The Data Protection Act 2018

Definitions

To assist working through and understanding this policy a number of key definitions need to be explained:

Adult is anyone aged 18 or over.

Adult at Risk is a person aged 18 or over who:

• Has needs for care and support (whether or not the local authority is meeting any of those needs);

and;

• Is experiencing, or is at risk of, abuse or neglect;

and;

• As a result of those care and support needs is unable to protect themselves from either the risk of, or the experience of, abuse or neglect.

Adults in need of care and support is determined by a range of factors including personal characteristics, factors associated with their situation, or environment and social factors. Naturally, a person’s disability or frailty does not mean that they will inevitably experience harm or abuse.

In the context of safeguarding adults, the likelihood of an adult in need of care and support experiencing harm or abuse should be determined by considering a range of social, environmental and clinical factors, not merely because they may be defined by one or more of the above descriptors.

Abuse is a violation of an individual’s human and civil rights by another person or persons. See section 4 for further explanations.

Adult safeguarding is protecting a person’s right to live in safety, free from abuse and neglect.

Capacity refers to the ability to make a decision at a particular time, for example when under considerable stress. The starting assumption must always be that a person has the capacity to make a decision unless it can be established that they lack capacity (MCA 2005). See Appendix 2 for guidance and information.

3. Types of Abuse and Neglect

There are different types and patterns of abuse and neglect, and different circumstances in which they may take place. The Care Act 2014 identifies the following as an illustrative guide and is not intended to be exhaustive list as to the sort of behaviour which could give rise to a safeguarding concern:

Self-neglect – this covers a wide range of behaviour: neglecting to care for one’s personal hygiene, health or surroundings and includes behaviour such as hoarding.

Modern Slavery – encompasses slavery, human trafficking, forced labour and domestic servitude. Traffickers and slave masters use whatever means they have at their disposal to coerce, deceive and force individuals into a life of abuse, servitude and inhumane treatment.

Domestic Abuse and coercive control – including psychological, physical, sexual, financial and emotional abuse. It also includes so called ‘honour’ based violence. It can occur between any family members.

Discriminatory Abuse – discrimination is abuse which centres on a difference or perceived difference particularly with respect to race, gender or disability or any of the protected characteristics of the Equality Act.

Organisational Abuse – including neglect and poor care practice within an institution or specific care setting such as a hospital or care home, for example, or in relation to care provided in one’s own home. This may range from one-off incidents to on-going ill-treatment. It can be through neglect or poor professional practice as a result of the structure, policies, processes and practices within an organisation.

Physical Abuse – including hitting, slapping, pushing, kicking, misuse of medication, restraint or inappropriate sanctions.

Sexual Abuse – including rape, indecent exposure, sexual harassment, inappropriate looking or touching, sexual teasing or innuendo, sexual photography, subjection to pornography or witnessing sexual acts, indecent exposure and sexual assault, or sexual acts to which the adult has not consented or was pressured into consenting.

Financial or Material Abuse – including theft, fraud, internet scamming, coercion in relation to an adult’s financial affairs or arrangements, including in connection to wills, property, inheritance or financial transactions, or the misuse or misappropriation of property, possessions or benefits.

Neglect – including ignoring medical or physical care needs, failure to provide access to appropriate health social care or educational services, the withholding of the necessities of life, such as medication, adequate nutrition and heating.

Emotional or Psychological Abuse – this includes threats of harm or abandonment, deprivation of contact, humiliation, blaming, controlling, intimidation, coercion, harassment, verbal abuse, isolation or withdrawal from services or supportive networks.

Not included in the Care Act 2014 but also relevant:

Cyber Bullying – cyber bullying occurs when someone repeatedly makes fun of another person online, or repeatedly picks on another person through emails or text messages, or uses online forums with the intention of harming, damaging, humiliating or isolating another person. It can be used to carry out many different types of bullying (such as racist bullying, homophobic bullying, or bullying related to special educational needs and disabilities) but instead of the perpetrator carrying out the bullying face-to-face, they use technology as a means to do it.

Forced Marriage – forced marriage is a term used to describe a marriage in which one or both of the parties are married without their consent or against their will. A forced marriage differs from an arranged marriage, in which both parties consent to the assistance of a third party in identifying a spouse. The Anti-social Behaviour, Crime and Policing Act 2014 make it a criminal offence to force someone to marry.

Mate Crime – a ‘mate crime’ as defined by the Safety Net Project as ‘when vulnerable people are befriended by members of the community who go on to exploit and take advantage of them. It may not be an illegal act but still has a negative effect on the individual.’ Mate Crime is carried out by someone the adult knows and often happens in private.

Radicalisation – the aim of radicalisation is to attract people to their reasoning, inspire new recruits and embed their extreme views and persuade vulnerable individuals of the legitimacy of their cause. This may be direct through a relationship, or through social media.

4. Signs and indicators of abuse and neglect

Abuse can take place in any context and by all manner of perpetrator. Abuse may be inflicted by anyone operating within or on behalf of the charity. Employees, volunteers, members and supporter stakeholders may suspect a service user is being abused or neglected and there are many signs and indicators. These include but are not limited to:

• Unexplained bruises or injuries – or lack of medical attention when an injury is present.

• Person has belongings or money going missing.

• Person is not attending / no longer enjoying or activities.

• Someone losing or gaining weight / an unkempt appearance.

• A change in the behaviour or confidence of a person. For example, a service user might behave differently and adversely in the presence of one person – friend, family member, carer – compared to when they are not present.

• They may self-harm.

• They may have a fear of a particular group or individual.

• They may tell you / another person they are being abused – i.e., a disclosure.

• Harassing of a service user, beneficiary, volunteer or member because they are or are perceived to have protected characteristics.

• The threatening of a service user, beneficiary, volunteer or member verbally or physically.

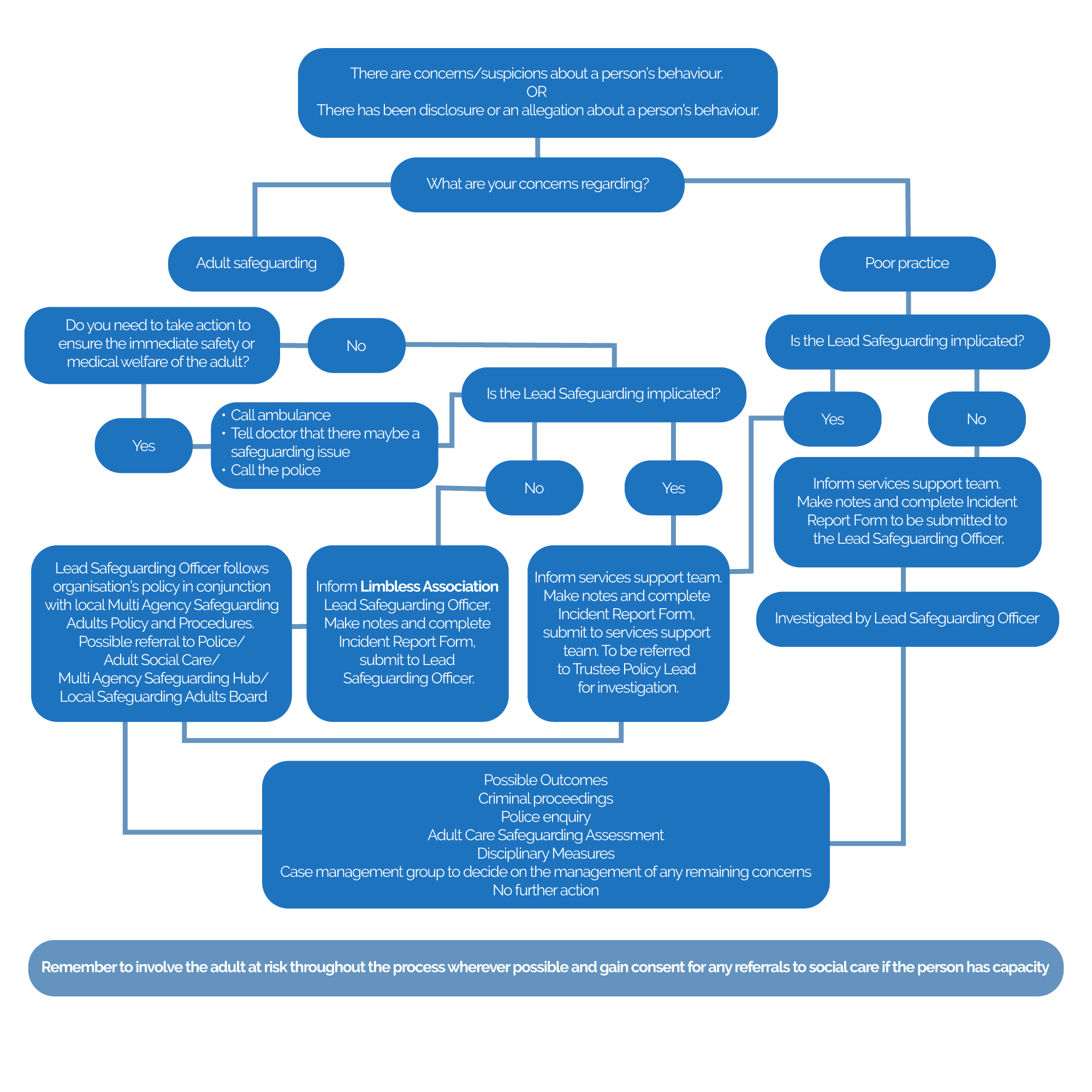

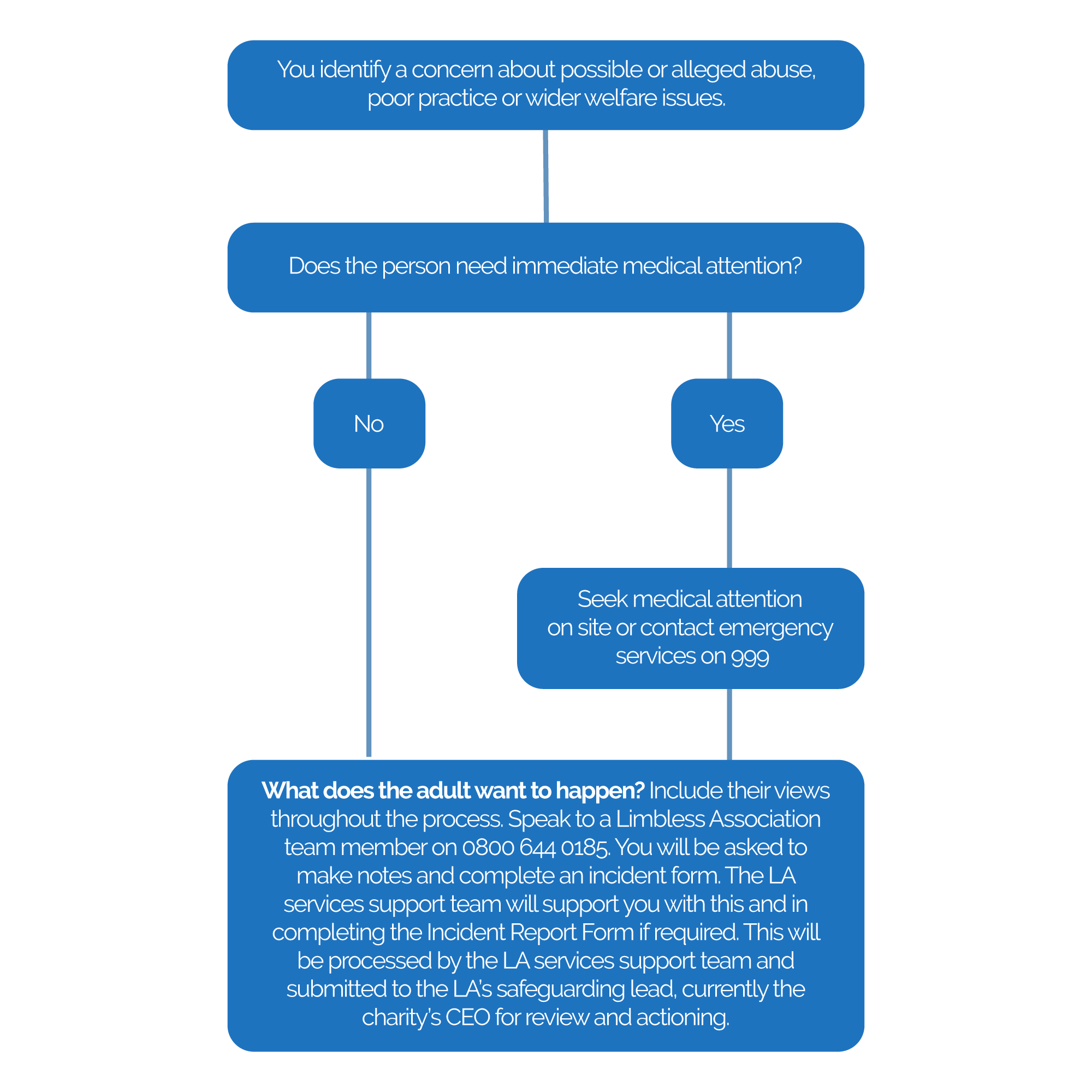

5. What to do if you have a concern, or if someone raises concerns with you.

• It is not your responsibility to decide whether or not an adult has been abused. It is, however, everyone’s responsibility to respond to and report concerns.

• If you are concerned someone is in immediate danger, contact the police on 999 straight away. Where you suspect that a crime is being committed, you must involve the police.

• If you have concerns and or you are told about possible or alleged abuse, poor practice or wider welfare issues you must report this to the Limbless Association Lead Safeguarding Officer, Limbless Association CEO.

• When raising your concern with the Lead Safeguarding Officer, remember Making Safeguarding Personal. It is good practice to seek the adult’s views on what they would like to happen next and to inform the adult you will be passing on your concern.

• It is important when considering your concern that you keep the person informed about any decisions and action taken, and always consider their needs and wishes.

6. How to respond to a concern

• Make a note of your concerns.

• Make a note of what the person has said using his or her own words as soon as practicable. Complete an Incident Form with the support of the services support team and submit to the Lead Safeguarding Officer.

• Remember to make safeguarding personal. Discuss your safeguarding concerns with the adult, obtain their view of what they would like to happen, but inform them it’s your duty to pass on your concerns to your Lead Safeguarding Officer.

• Describe the circumstances in which the disclosure came about.

• Take care to distinguish between fact, observation, allegation and opinion. It is important that the information you have is accurate.

• Be mindful of the need to be confidential at all times. This information must only be shared with the services support team and your Lead Safeguarding Officer and others on a need-to-know basis.

• If the matter is urgent and relates to the immediate safety of an adult at risk then contact the emergency services immediately and then immediately notify the LA’s Lead Safeguarding Officer.

Roles and responsibilities of those within Limbless Association

Limbless Association is committed to having the following in place:

• Lead Safeguarding Officer to produce and disseminate guidance and resources to support the policy and procedures.

• A clear line of accountability within the organisation for work on promoting the welfare of all adults.

• Procedures for dealing with allegations of abuse or poor practice against members of staff and volunteers.

• A Steering Group comprising the Limbless Association CEO and nominated Trustees will collectively and effectively deal with issues, manage concerns and refer to a disciplinary panel where necessary (i.e. where concerns arise about the behaviour of someone within the Limbless Association)

• A Disciplinary Panel will be formed as required for a given incident, if appropriate and should a threshold be met.

• Arrangements to work effectively with other organisations to safeguard and promote the welfare of adults, including arrangements for sharing information.

• Appropriate whistle blowing procedures and an open and inclusive culture that enables safeguarding and equality and diversity issues to be addressed. Adherence to the Limbless Association Equality and Diversity and Whistleblowing policies.

• Clear codes of conduct are in place for employees, volunteers and members.

8. Good practice, poor practice and abuse

Introduction

It can be difficult to distinguish poor practice from abuse, whether intentional or accidental.

It is not the responsibility of any individual involved in the Limbless Association to make judgements regarding whether or not abuse is taking place. However, all Limbless Association personnel have the responsibility to recognise and identify poor practice and potential abuse, and act on this if they have concerns.

Good practice

Limbless Association expects that all employees and volunteers comply as follows:

• Adopt and endorse the Limbless Association Code of Conduct and organisational values.

• Have completed a course in basic awareness in safeguarding and working with Adults at Risk.

• Where employees or volunteers are supporting the Volunteer Visitor network additional safeguarding training relating to this work will be undertaken.

Where participating in Limbless Association outreach activities or being supported by LA services all involved should:

• Aim to ensure that service users are supported in a friendly, empathetic and inclusive environment.

• Everyone should promote an environment that thrives on mutual respect and understanding.

• Not tolerate the use of prohibited or illegal substances.

• Treat all adults equally and preserve their dignity. This includes giving more and less able, physically and emotionally, members of a group similar attention, time and respect.

9. Relevant Policies

This policy should be read in conjunction with the following policies of the Limbless Association:

• Equality and Diversity

• Whistle Blowing

• Equal Opportunities

• Social media

• Complaints

• Disciplinary

10. Further Information

Policies, procedures and supporting information are available by contacting the Limbless Association on 01277 402331 or emailing enquiries@limbless-association.org

Lead Safeguarding Officer: Deborah Bent, Chief Executive Officer. Tel. 01277 402331

Email: deborah@limbless-association.org.

Review date: October 2024

This policy will be reviewed annually or sooner in the event of legislative changes or revised policies and best practice.

Appendix 1

Guidance and information

Making Safeguarding Personal

There has been a cultural shift towards Making Safeguarding Personal within the safeguarding process. This is a move from prioritising outcomes demanded by bureaucratic systems. The safeguarding process used to involve gathering a detailed account of what happened and determining who did what to whom. Now the outcomes are defined by the person at the centre of the safeguarding process.

The safeguarding process places a stronger emphasis on achieving satisfactory outcomes that take into account the individual choices and requirements of everyone involved.

“What good is it making someone safer if it merely makes them miserable?” – Lord Justice Mundy, “What Price Dignity?” (2010)

What this means in practice is that adults should be more involved in the safeguarding process. Their views, wishes, feelings and beliefs must be taken into account when decisions are made.

The Care Act 2014 builds on the concept, stating that “We all have different preferences, histories, circumstances and lifestyles so it is unhelpful to prescribe a process that must be followed whenever a concern is raised.”

However, the Act is also clear that there are key issues that should be taken into account when abuse or neglect are suspected, and that there should be clear guidelines regarding this.

https://www.local.gov.uk/topics/social-care-health-and-integration/adult-social-care/making-safeguarding-personal

Capacity – Guidance on Making Decisions

The issue of capacity or decision making is a key one in safeguarding adults. It is useful for organisations to have an overview of the concept of capacity.

We make many decisions every day, often without realising. We make so many decisions that it’s easy to take this ability for granted.

But some people are only able to make some decisions, and a small number of people cannot make any decisions. Being unable to make a decision is called “lacking capacity”.

To make a decision we need to:

• Understand information

• Remember it for long enough

• Think about the information

• Communicate our decision

A person’s ability to do this may be affected by things like learning disability, dementia, mental health needs, acquired brain injury, and physical ill health.

The Mental Capacity Act 2005 (MCA) states that every individual has the right to make their own decisions and provides the framework for this to happen.

The MCA is about making sure that people over the age of 16 have the support they need to make as many decisions as possible.

The MCA also protects people who need family, friends, or paid support staff to make decisions for them because they lack capacity to make specific decisions.

Our ability to make decisions can change over the course of a day.

Here are some examples that demonstrate how the timing of a question can affect the response:

• A person with epilepsy may not be able to make a decision following a seizure.

• Someone who is anxious may not be able to make a decision at that point.

• A person may not be able to respond as quickly if they have just taken some medication that causes fatigue.

In each of these examples, it may appear as though the person cannot make a decision. But later in the day, presented with the same decision, they may be able to at least be involved.

The MCA recognises that capacity is decision-specific, so no one will be labelled as entirely lacking capacity. The MCA also recognises that decisions can be about big life-changing events, such as where to live, but equally about small events, such as what to wear on a cold day.

To help you to understand the MCA, consider the following five points:

1. Assume that people are able to make decisions, unless it is shown that they are not. If you have concerns about a person’s level of understanding, you should check this with them, and if applicable, with the people supporting them.

2. Give people as much support as they need to make decisions. You may be involved in this – you might need to think about the way you communicate or provide information, and you may be asked your opinion.

3. People have the right to make unwise decisions. The important thing is that they understand the implications. If they understand the implications, consider how risks might be minimised.

4. If someone is not able to make a decision, then the person helping them must only make decisions in their “best interests”. This means that the decision must be what is best for the person, not for anyone else. If someone were making a decision on your behalf, you would want it to reflect the decision you would make if you were able to.

5. Find the least restrictive way of doing what needs to be done.

Remember:

• You should not discriminate or make assumptions about someone’s ability to make decisions, and you should not pre-empt a best-interests decision merely on the basis of a person’s age, appearance, condition, or behaviour.

• When it comes to decision-making, you could be involved in a minor way, or asked to provide more detail. The way you provide information might influence a person’s ultimate decision. A person may be receiving support that is not in-line with the MCA, so you must be prepared to address this.

Consent and Information Sharing

Employees and volunteers within should always share safeguarding concerns in line with their organisation’s policy, usually with their safeguarding lead or welfare officer in the first instance, except in emergency situations. As long as it does not increase the risk to the individual, the worker or volunteer should explain to them that it is their duty to share their concern with their safeguarding lead or welfare officer.

The safeguarding lead or welfare officer will then consider the situation and plan the actions that need to be taken, in conjunction with the adult at risk and in line with the organisation’s policy and procedures and local safeguarding adults board policy and procedures.

To make an adult safeguarding referral you need to call the local safeguarding adults team. This may be part of a MASH (Multi-Agency Safeguarding Hub). A conversation can be had with the safeguarding adults team without disclosing the identity of the person in the first instance. If it is thought that a referral needs to be made to the safeguarding adults team, consent should be sought where possible from the adult at risk.

Individuals may not give their consent to the sharing of safeguarding information with the safeguarding adult’s team for a number of reasons. Reassurance, appropriate support and revisiting the issues at another time may help to change their view on whether it is best to share information.

If they still do not consent, then their wishes should usually be respected. However, there are circumstances where information can be shared without consent such as when the adult does not have the capacity to consent, it is in the public interest because it may affect other people or a serious crime has been committed. This should always be discussed with your safeguarding lead and the local authority safeguarding adults team.

If someone does not want you to share information outside of the organisation or you do not have consent to share the information, ask yourself the following questions:

• Is the adult placing themselves at further risk of harm?

• Is someone else likely to get hurt?

• Has a criminal offence occurred? This includes: theft or burglary of items, physical abuse, sexual abuse, subject to financial abuse or harassment.

• Is there suspicion that a crime has occurred?

If the answer to any of the questions above is ‘yes’ – then you can share without consent and need to share the information.

When sharing information there are seven Golden Rules that should always be followed.

1. Seek advice if in any doubt

2. Be transparent – The Data Protection Act is not a barrier to sharing information but to ensure that personal information is shared appropriately; except in circumstances whereby doing so places the person at significant risk of harm.

3. Consider the public interest – Base all decisions to share information on the safety and well-being of that person or others that may be affected by their actions.

4. Share with consent where appropriate – Where possible, respond to the wishes of those who do not consent to share confidential information. You may still share information without consent, if this is in the public interest.

5. Keep a record – Record your decision and reasons to share or not share information.

6. Accurate, necessary, proportionate, relevant and secure – Ensure all information shared is accurate, up-to-date and necessary, and share with only those who need to have it.

7. Remember the purpose of the Data Protection Act (DPA) is to ensure personal information is shared appropriately, except in circumstances whereby doing so may place the person or others at significant harm.

Appendix 2

Legislation and Government Initiatives

The Sexual Offences Act introduced a number of new offences concerning vulnerable adults and children. www.opsi.gov.uk

Its general principle is that everybody has capacity unless it is proved otherwise, that they should be supported to make their own decisions, that anything done for or on behalf of people without capacity must be in their best interests and there should be least restrictive intervention. www.dca.gov.uk

Safeguarding Vulnerable Groups Act 2006

Introduced the new Vetting and Barring Scheme and the role of the Independent Safeguarding Authority. The Act places a statutory duty on all those working with vulnerable groups to register and undergo an advanced vetting process with criminal sanctions for non-compliance. www.opsi.gov.uk

Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards

Introduced into the Mental Capacity Act 2005 and came into force in April 2009. Designed to provide appropriate safeguards for vulnerable people who have a mental disorder and lack the capacity to consent to the arrangements made for their care or treatment, and who may be deprived of their liberty in their best interests in order to protect them from harm.

Disclosure & Barring Service 2013

Criminal record checks: guidance for employers – How employers or organisations can request criminal records checks on potential employees from the Disclosure and Barring Service (DBS). www.gov.uk/dbs-update-service

The Care Act 2014 – statutory guidance

The Care Act introduces new responsibilities for local authorities. It also has major implications for adult care and support providers, people who use services, carers and advocates. It replaces No Secrets and puts adult safeguarding on a statutory footing.

Making Safeguarding Personal Guide 2014

This guide is intended to support councils and their partners to develop outcomes-focused, person-centred safeguarding practice.